A set of basic beliefs commonly held among a group of people; the baseline of knowledge an individual is expected to have within their own community; simple facts drawn from self-evident conclusions; intrinsically subjective, i.e. “You ought to have known that, it’s common sense”; the aggregate of collective knowledge (does that mean the Internet is common sense?); a mushy term that is really hard to define in any satisfactory way.

Common sense might just be inherently vague and the exercise of trying to define it inherently silly. But I hope to show that in the context of overcoming our national crisis with food, a robust and shared notion of common sense has an important place, so bear with me.

Depending on how you define common sense, its opposite could either be rash stupidity or a set of contested facts that require explanation. Lets focus on the latter for the purposes of this post and say that the opposite of common sense is confusing information that is in no way intuitive. If you’ve spent any time today skimming The Atlantic, the health section of The New York Times or the abstracts of re-posted articles on your Facebook newsfeed, you’ll have probably encountered this kind of information.

Examples:

1) The Atlantic’s The Great Salt Debate: So Bad? by Travis M. Andrews in which salt defender Gary Taubes explains that “people believe salt is bad simply because that seems logical, even if it isn’t.”

2) Foodnavigator-USA.com’s New research into exactly where Americans’ calories are coming from throws up surprising results by Elaine Watson, cites a study which found, “contrary to popular belief,” that fast food and junk food accounts for less caloric intake than previously thought.

3) The New York Times’ Don’t Take Your Vitamins by Paul A. Offit, which discusses the “antioxidant paradox,” where taking too many doses of antioxidants in the form of supplemental vitamins can be harmful to your health.

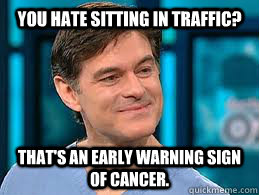

Eye-catching headlines like these introduce articles that are often as full of surprising data as they are void of measured assessment of the cited study’s structure, findings, and funders. These are the viral articles that get shared the most and satisfy our browsing curiosity by leaving us with the feeling that we learned something new, because it was unexpected and unconventional and deviated from common sense. We rush to click the share button as if it would earn us a virtual merit badge for being the first in our social circles whose worldview has been enriched with the nuance of the counterintuitive.

But here’s the thing: despite everything I just said above about these eye-catching articles, I do actually agree with one of them. The Atlantic did a terrible job of making it clear to its readers that while a handful of salt defenders being paid by the Salt Institute want salt consumption to stay the same, the American Heart Association, United States Department of Agriculture, Center for Disease Control, and even the Institute of Medicine think that for 99% of Americans (yes that means you!) consumption needs to go down. And although Foodnavigator-USA did point out at the end of their article that the National Restaurant Association funded the study cited in the headline, i.e., the organization that stands to gain the most positive PR from the findings, who is going to read that far?

The New York Times article, however, was right on. I agree completely that the vitamin and supplement industry is a total racket. Excepting specific recommendations from your doctor, eating a balanced diet (mostly fruits and vegetables, whole grains, some dairy, and fish for those EPA and DHA omega-3s) is almost always a better way of getting what you need than taking isolated vitamins and minerals in pill form. (Note, this isn’t to say the New York Times always gets it right. Earlier this year Pam Belluck’s article Study Suggests Lower Mortality Risk for People Deemed to Be Overweight forgot to mention that the study didn’t adjust for the test subjects who had lost weight because they were already sick or dying at the beginning of the study. Meaning the data didn’t prove that overweight people live longer than people whose B.M.Is were in the recommended ranges, it just confirmed the no-brainer that serious illness often comes with serious weight loss.)

What does it mean that out of these similarly formatted articles, all of which come from fairly reputable sources, only one offers useful advice? It’s a problem I am sure you’ve also encountered at some point, browsing online, flipping through the schizophrenic pages of a fashion magazine, or watching Dr. Oz at the gym: how are we supposed to navigate all the nutrition information being thrown at us and separate the good information from the bad?

There is another setting in which this question is sure to arise. An environment full of overwhelming and contradictory information describes a Facebook newsfeed as well it describes the uncharted aisles in the middle of the supermarket. Thanks to all those messy and misleading labels, shopping for food pretty is much the worst. You basically need a calculator to do the serving size math and work out how much fiber, sugar, fat and other ingredients are in your shopping cart. You also need to know how many of those things you are actually supposed to have a day to begin with. A PhD in longass words helps too, because how else is anyone supposed to know that Triplodextrins are refined sugars, Suchrolimaseors are useless artificial fibers, and why is there fire retardant in this energy drink? Also, you are balancing the limited resources of patience, will power, time, and money and doing it in a building without windows (this is on purpose, so you lose track of time) and large displays of junk food at the end of every aisle (this is on purpose, to grind away at your will power). And finally, you are doing all of this to keep you and whomever else you are responsible for feeding alive, preferably for the average healthy lifespan of a North American adult (ideally from your grandparents’ generation, since health stats during the last 30 years haven’t been so great). I spend a lot of time learning and reading about this stuff, and still I occasionally find myself in the aisle with the sugar-free workout energy water enhancers and olestra flavored low-fat Pringle’s.

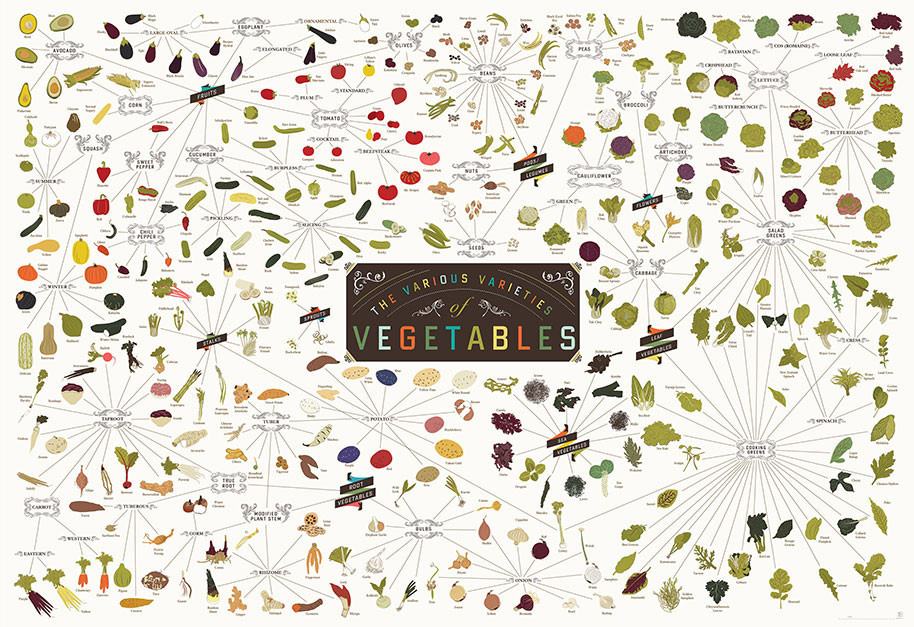

We try to keep our heads above water with the handful of nutrition facts we happen to remember, things like: antioxidants and flavanols are good for you, eating lots of fruits and vegetables is important, and Vitamin C helps fight colds. But these facts can sometimes run away from us, leading to conclusions like “I should eat dark chocolate because it has antioxidants and flavanols, drink V8 Fusion because the label says each serving of juice has a cup of fruits and vegetables in it, and buy Emergen-C December through February to boost my immune system.” But eating chocolate because of its purported health benefits is crazy, because chocolate isn’t healthy. Its delicious, its fun to eat, and in small amounts its fine. But that is different from healthy. Water and spinach are healthy. You would have to consume a lot of either of them before their benefits to your health were in any way compromised. You only need a little too much dark chocolate before the antioxidants in them are totally trumped by the calories and sugar and the precedent you set up in which things you want with a little qualification become things you need. As for those fruits and veggies, at 24g of sugar per serving (Coke has 27g), V8 Fusion’s pulverized, powdered, and reconstituted vegetable matter is as good as the plastic it comes in. And Vitamin C? Unless you are training for a marathon you probably don’t need more Vitamin C than you can get from an orange. Just eat an orange. Or a bell pepper or broccoli or kale or strawberries or cauliflower or kiwi or Brussels sprouts, which all have tons of naturally occurring Vitamin C.

To summarize: we live in a chaotic food environment. Most of the time it feels like even with complete access to an endless amount of food information, we are ill-equipped to meet one of the most basic requirements for survival: feeding ourselves. No other animal manages to make itself as sick as we do by eating. Probably because no other animal is as good at creativity, productivity, and deceit.

What seems to be missing in our relationship with food is a guiding principle, some larger philosophy to organize our food knowledge around and to help us sidestep the questionable information coming out of People magazine.

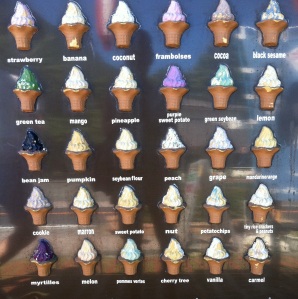

And the first step to establishing that guiding principle? Recognizing that every diet decision depends on your individual context. Your weight, your health, your medical history, the time of day, your level of physical activity, the part of the world you find yourself in, the season, your income, how many other people you have to feed and a laundry list of qualifiers that only you know about yourself.

I’m guessing this is not the answer you were hoping for. It probably seems like taking all these factors—lets call it your health context—into account is going to make feeding yourself harder, not easier. But here’s the thing: your health context is not nearly as fragmented as the nutrition facts spilling out of Oprah’s empire or Special K advertisements. We are constantly being bombarded by nutritional information produced by people who have no interest in our well-being. No, none. Not even the people at Kashi. They have shareholders that they are accountable to, they need to grow every quarter, and they will do it at your expense. Food manufactures and the people they pay to advertise their products hype counterintuitive studies, label their products with patent nonsense, and trick you into wandering supermarket aisles for hours because are have a vested interest in keeping you confused and overwhelmed. That way, next time they début a useless food product with high profit margins, packed with fat, sugar, and salt, and plastered with promises (Protein! Fiber! Acai! Coconut Water!) and tell you that it will make up for all your previous food errors, you will be more likely to break down and buy their argument and their product. The longer we stay lost in the muck and details of these contradictory food facts, the longer those industries trying to sell us shit win.

But you, you are invested in your own health. This is the underlying and unifying fact of your health context. Remember this each time you choose what food to buy or vitamins to take. Rather than complicate your purchasing decisions, it should simplify them.

Obviously, just caring about your health isn’t going to be enough. If it were, we wouldn’t be seeing the current rates of heart disease, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, childhood obesity and so on.

So what else goes into a guiding principle of food?

This is where I see common sense coming back into the picture. What do I mean by common sense? It’s a story from your grandma’s farm, it’s something you learned about another country, it’s what makes up the bedrock of a culture’s cuisine, it’s what feels right all the time, it’s what worked for you after years of doing it wrong, it’s what you wouldn’t be embarrassed to explain to someone on the other side of the world, it’s what’s different for everyone but also the same, it isn’t going to change with the next fad diet, it’s going to keep you and your kids healthy and alive, it’s sustainable and affordable and simple, it’s elusive but it isn’t a unicorn, it’s yours.

I can’t tell you exactly what your common sense is, but I believe that by talking about a common sense vision of food and sharing individual food knowledge we make our communal consumer identity stronger and more resilient against the exhausting and endless misinformation that comes out of the processed-food-industrial-complex. I think more and more people are looking for and returning to this kind of food knowledge and when I hear people talk about a new ‘food movement,’ I feel optimistic for this reason.

OK, that’s nice and fuzzy, I hear you thinking, but what about some examples?

Well the poster above, put out by the US Food Administration during World War I, is a good start. These rules are flexible enough to mesh with the idiosyncrasies of each family’s dinner table. When I first saw this poster, I was struck by how straightforward and useful the advice seemed. Just good common sense.

Another is Michael Pollan’s oft quoted “Eat food. Not too much. Mainly fruits and veggies.”

Why are these suggestions different from what is on the back of a box of breakfast cereal? Maybe because Michael Pollan doesn’t make money every time you hear those three sentences and the Federal government, while it did have an agenda to limit food waste during a war, also had a duty to maintain the health and wellness of its citizens. That seems to be another common quality in common sense—it tends to come from people who aren’t trying to sell you something.

I believe in common sense. I think that the most compelling food movement advocates—Marion Nestle, Michael Pollan, Jamie Oliver, Michelle Obama—also believe in common sense. Yes, they sometimes say controversial things and everyone won’t always agree on the details. But we have forever to quibble over facts, like which fats are good and which are bad, what is a responsible serving size, how much red meat should you eat, is corn syrup a natural ingredient and seriously, what is the deal with women taking calcium supplements. But these details shouldn’t get in the way of overall balance, moderation, and a less manic relationship with our food.

We kept ourselves alive with way fewer resources for thousands of years and while you would be right to point out that quality of life and length of life were shorter then, common sense would dictate that somewhere between starving with no access to modern medical care and eating whatever you want whenever you want, no matter the fat, sugar and salt content or season and being totally dependent on modern medical care because of it—somewhere between those two poles is a healthy human who lives a good life and finds joy in food without really having to think about it.

I recognize that the constraints of income and access to fresh produce pretty much make the common sense point moot for some families. I wrote this post with the intention of empowering consumers and encouraging healthier choices where and when possible, knowing that it wouldn’t even begin to cover all of the obstacles consumers face getting healthy food on the table.

I also hope that, in the context of my other posts, this will not be construed as blaming consumers for lacking common sense as they continue to struggle with food purchases, meal preparation and their health. I take it as a given that the food landscape we currently inhabit is in no way set up in favor of consumers. Ultimately, while the responsibility shouldn’t be on us to outwit the multimillion dollar ad campaigns of large food companies and make up for the relaxed regulation of the agencies mandated with keeping our food supply safe, if we wait on industry and government action, we will miss out on the chance to take back our shopping carts and our health and live with the blissful privilege of not having to think so much about food anymore.

Pingback: I’m going out on a limb and predicting Glitter Wine in 2014 | Sustaining Starter